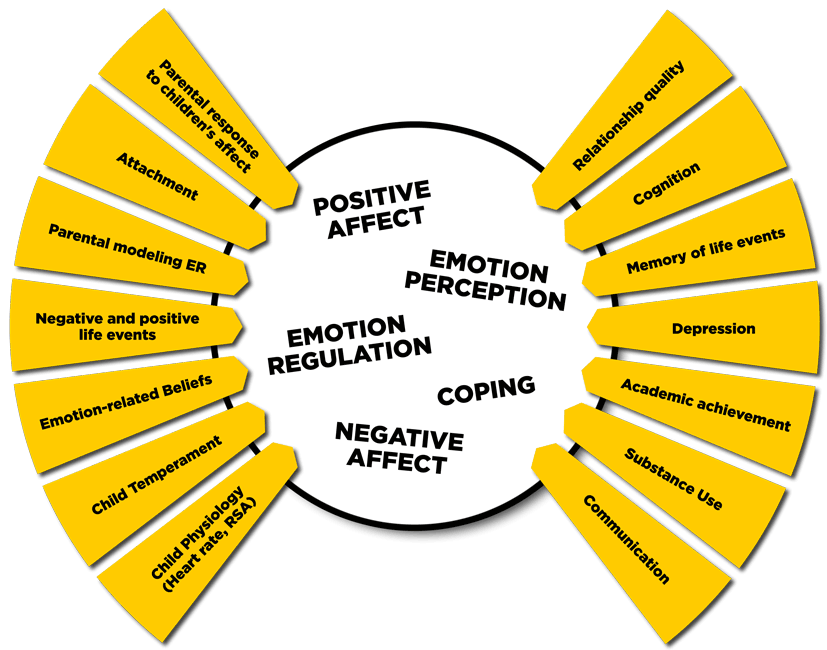

In the IDEA Lab, we study people’s emotional lives. A unique aspect of the lab is that we have often focused on positive affect or happiness and how people seek out or regulate positive emotions and pursue hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. We also try to better understand how and why people develop the emotion beliefs or regulatory strategies that they do by studying factors like attachment, familial socialization, and history of depression. For the last 10-15 years, we have also studied social media use to better understand how these platforms meet people’s socio-emotional needs.

Areas of Research

- Social Media Use in Teens, College Students, and Families

- Like with other topics, we often take an individual differences approach to determine why people choose to use different platforms/modes of communication or why they react differently to the same platforms. For example, we found that for college students higher in avoidant attachment, texting with their romantic partner was related to more satisfaction and intimacy and support, but for less avoidantly attached people, texting was not related to higher relationship quality (Morey et al., 2013). Thus, people who are more avoidantly attached may like texting for its limited communication of emotion and spontaneity.More recently, we studied how high school aged teens may be differentially responsive to social media. We found that extraversion is a protective factor in that highly extraverted adolescents do not report elevated depressive symptoms when using Instagram, but teens low or average on extraversion do report higher levels of depressive symptoms when using Instagram frequently. We also found that adolescents who tend to feel badly when using social media reported more depressive symptoms when frequently on TikTok but for those not prone to negative reactions, TIkTok use was unrelated to depressive symptoms (Gentzler et al, 2023).

- Emotion Regulation in Children, Adolescents, and Adults – What do people do (after good things happen or how do they seek happiness) and what are ramifications of these behaviors?

- Measurement work. We have developed measures to assess how people respond to positive events. The initial survey (the PEARS/Positive Events And Responses Survey; Gentzler, Palmer, & Ramsey, 2016) includes vignettes and assesses participants’ likelihood of responding in various ways. There are slightly different versions for adults (PEARS-A; Ramsey & Gentzler, 2014) and youth (PEARS-Y). With these measures, broader scales are often created – either savoring and dampening (Ramsey & Gentzler, 2014) or natural savoring, intentional savoring, and dampening (Gentzler et al., 2016; Palmer & Gentzler, 2019). Subscales can also be analyzed on their own, such as just examining bragging (Palmer, Ramsey, Morey, & Gentzler, 2016), reflection, gratitude, etc. In addition, we have a version (PAARS) without vignettes that asks about participants’ responses to positive affect rather than specific positive events.

- Implications of ER strategies. We often investigate correlates or outcomes of particular emotion regulation strategies. For example, we assessed cognitive and emotional reactions after failure based on children’s level of rumination, which has implications for school performance (Gentzler, Wheat, Palmer, & Burwell, 2013). With positive affect regulation, young adolescents who savored a positive life event had higher levels of sustained positive affect about the event, even when controlling for initial positive reactions (Gentzler, Morey, Palmer, & Yi, 2012). Additionally, children who more often dampened their positive events were rated as having more internalizing and externalizing problems by their parents.

- The pursuit of happiness, well-being, or positive affect. Happiness is often considered one of the most important aspects of life (as well as parents’ # 1 wish for their children), yet we do not know a lot about the pursuit of it. There are many benefits to feeling positive affect and happiness (Fredrickson, 1998; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005; Ramsey & Gentzler, 2015), but if people prioritize their own happiness too much, it could be problematic (Mauss, Tamir, Anderson, & Savino, 2011). We published findings from 3 studies indicating that youth who excessively value their happiness report higher levels of depressive symptoms (Gentzler, Palmer, Ford, Moran, & Mauss, 2019). We also are investigating youth’s pursuit of hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. In an NIH-funded project, we are studying these processes longitudinally in a sample of 9th graders, with collaborators from WVU and other universities: Amy Root, Christa Lilly, Iris Mauss, Alfgeir Kristjansson, Maria Kovacs, and Veronika Huta.

- Development of Emotion Regulation – What factors might contribute to individual or group differences in ER? How can we promote children’s emotional well-being?

- Beliefs about emotions. We have been studying how people think about emotions as a potentially important predictor of emotion socialization, emotion regulation, and adjustment. For example, we applied Tsai’s concept of ideal affect and affect valuation theory (Tsai, 2007) to parental emotion socialization of children’s positive affect. Even within a culturally homogenous sample, we found that mothers who want their child to feel more high-arousal positive emotions (excitement, etc.) are more likely to encourage behaviors (celebrating) likely to elicit those emotions, whereas mothers who want their child to feel low-arousal positive emotions encourage different responses (e.g., being affectionate; Gentzler, Palmer, Yi, Root, & Moran, 2018). In Jennifer Morey’s dissertation, she found that parents who have more positive beliefs about emotions (meta-emotion philosophy) are more accurate in reading children’s emotions expressions and have more desire to interact with children (Morey & Gentzler, 2017).

- Attachment style. One’s early relationship with one’s parents/caregivers is especially important and teaches children if they can rely on others for support and intimacy, and how to regulate attachment needs accordingly. Our lab often studies how attachment is related to emotion regulation. For example, children who are more securely attached to their fathers report more savoring of positive life events (Gentzler, Ramsey, Yi, & Palmer, 2014). Mothers who report more avoidant attachment report feeling less positively and encouraging less savoring when their children experience positive events (Gentzler, Ramsey, & Black, 2015). In older adults, Palmer and Gentzler (2018) found that more insecurely attached adults (more avoidant or more anxious) did not benefit from savoring interpersonal positive events like other adults who are more secure (less avoidant or anxious).

- Parental socialization. Parents are thought to have a major influence on children’s developing emotion regulation through shared genes and environment. Our lab has investigated how parents or caregivers may teach or socialize emotion regulation in their children. We developed a measure, Parents’ Reactions to Children’s Positive Events (PRCPE; Gentzler, Ramsey, & Black, 2015), to capture various ways that parents may encourage or coach their child to savor or dampen positive affect. We edited a quartet of papers for Social Development on parental socialization of children’s positive affect regulation and published an integrative paper discussing next steps for this research (Gentzler & Root, 2019).

- Emotion Regulation in Particular Populations

- Emotion regulation and related attitudes and abilities in actors. As part of a collaborative project with Roger Smart, we investigated actors’ emotion beliefs and abilities. Given how integral emotions are to acting, we expected that theatre majors may have a greater emotion understanding and more skills (emotion perception, awareness, regulation, etc.) compared to college students without an acting background. We found some support for our hypotheses (Gentzler, DeLong, & Smart, 2019) and want to test similar hypotheses with youth.

- Emotion regulation in parents. Given that parenting can be challenging and full of emotionally-evocative situations, parents’ emotion regulation is critically important. For example, Tyia Wilson investigated how parents and adolescents’ emotion regulation predicts parents’ happiness. In a recent publication, former undergraduate Kaley Morrow reported on how mothers with elevated depressive symptoms are more likely to dampen their own positive emotions, and are less likely to savor their own or their child’s positive emotions or events.

- Emotions in older adults. A couple of former students, Cara Palmer and Megan Ramsey, completed studies on how people’s emotion regulation varies with age. Specifically, Ramsey and Gentzler (2014) found that, contrary to expectations, older adults did not report more savoring than middle-aged and younger adults and savoring did not account for older adults’ higher levels of wellbeing. Palmer and Gentzler (2019) further advanced this research by showing that older adults savor less than middle-aged and young adults, and that older adults’ emotional goals (desiring less high-arousal positive affect, and less motivation to pursue hedonia) can explain their lower tendency to savor or to benefit from savoring, even when using an experimental condition.